As a side project I’ve been working on a portable Python program to find if specific people, using facial recognition, are in a collection of images. The idea for this grew out of a joke but the more I thought about it I realized it had some real applications.

A co-worker of mine was having trouble finding images of specific individuals within a large folder of images. Over the years this folder had gotten overgrown and photos were in random sub-folders sorted by date, location, or event. It was hard to find photos of specific people without digging through a lot of images to see if they were in them. I jokingly suggested we use some facial recognition software to comb through the folder and just flag all instances of the person they were looking for. I held on to the idea over the next few days thinking about how something like this would function.

The idea itself is pretty boilerplate stuff for any image tool, like Google Photos or on Facebook. These will recognize the faces and do all the heavy lifting for you. My real interest lay in situations where having an offline solution to this problem would be useful. Family pictures on a parent’s computer or in this case employee photos not part of a unified imaging solution. I imagined there was some utility being able to throw in a USB drive, launch a script, and identify photos of interest based on looking for specific faces.

Table of Contents

Requirements

Following a familiar pattern I jotted requirements of what such a system would look like.

- Needed an image processing library capable of facial detection and recognition.

- It should be able to learn faces generically from reference photos. I didn’t want to have to build models for every individual

- Portability. That means it should run alone from something like a USB drive without having to install any libraries on a computer.

As I would come to find out requirements 1 and 2 were relatively easy. It was the portable piece of this project that proved to be the hardest to implement.

Facial Detection and Recognition

There are a lot of Python libraries available for facial detection and recognition. Detection is the process of deciding if something is either a face or not a face in an image. Recognition is the added step of identifying who’s face. This is a problem that’s been researched and solved numerous times over. All I really needed to do was evaluate which library best suited what I was looking to do. I ended up deciding the Deepface library would work the best for this project.

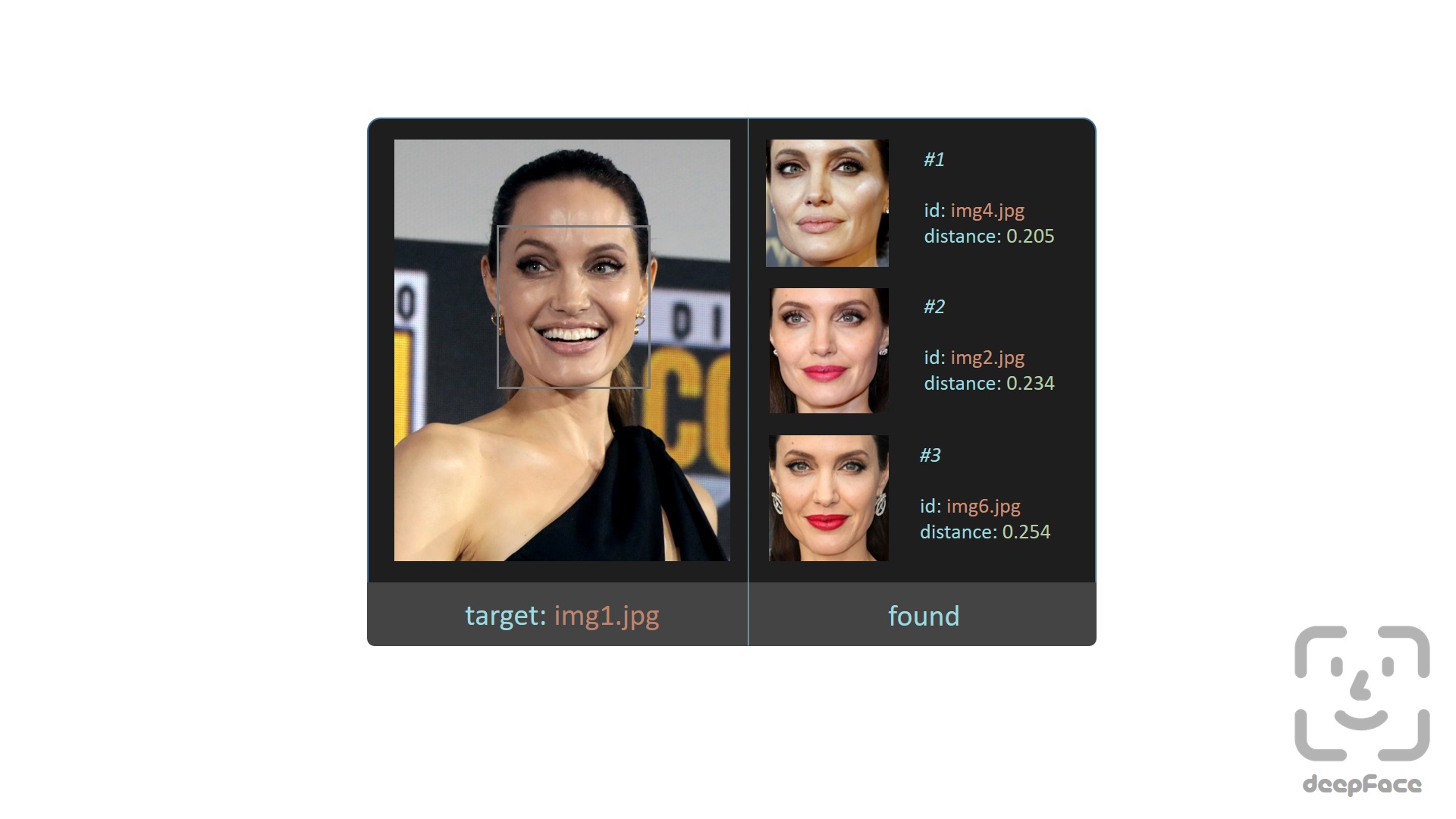

Deepface is a unique library in that it combines many different facial recognition and detection models into one library. This gives the option of swapping out models quickly if you want to fine-tune results. It also allows you to point to a set of reference images that are used to build the detection model. This is key since you may want to swap out who exactly you’re looking for in a set of photos. Some boilerplate code almost directly from the Deepface README shows how quickly this can be done.

model = "Facenet512" # the model to use, there are 8 choices

"""

img_path is the path to the image you want to check

db_path is the reference image directory

"""

dfs = DeepFace.find(img_path = "img1.jpg", db_path = "C:/workspace/my_db", model_name=model)

# the result returns an array of Pandas dataframes, each representing a face within the image

for df in dfs:

distance = df.loc[:,f"{model}_cosine"].min()

if(distance < .20):

"Found a match"

break

In the above example an array of Dataframes is returned, each one matching one face found in the image. Each dataframe contains various metrics, I use the cosine as that seemed the most accurate in testing. This metric is a numerical value representing how different the face in the image is from the reference images. In this case “different” is a mathematical representation of how different they are. The lower this number, the more likely the face is the same person as the reference photos. Obviously there is some room for error here, I found .20 to be a good threshold. Since a person can look slightly different between photos (lighting, facial expression, hair length, age) the more reference photos you provide the better the results tend to be.

Using this I was able to pretty quickly throw together a script to iterate through a directory finding images, and then pass them on to be evaluated. I added arguments for the folder of reference images, and the model you want to use. At the end it writes to the screen a list of images Deepface thinks are good matches. So far so good!

Parallel Processing

Running the Deepface process on a lot of images can be very time consuming. This isn’t the sort of thing where you’re going to churn through a five-hundred images in 5 minutes - far from it. In testing I noticed it took about 4-6 seconds per image. This value is somewhat dependent on the number of people in an image, the type of CPU, etc. Given that a portable solution wouldn’t have Google or Facebook levels of GPUs available I knew time would be a trade-off but still wanted it to go a bit faster.

Python has support for both multi-threading and multi-processing. I won’t pretend to be an expert on these but they both deal with dividing up program execution in different ways. Towards Data Science has a good write-up going through the concrete differences. For this particular problem multiprocessing is a good fit as image processing is a CPU intensive task. Python has a dedicated multiprocessing module but I chose to use the joblib Python library. It is a nice wrapper around the native functions and got me to an end result faster with only one more added dependency. A basic example using joblib would be:

from joblib import Parallel, delayed

# meaningless function to do some work

def square(i):

return i * i

# use n_jobs to specify how many parallel jobs to run at the same time

results = Parallel(n_jobs=3)(delayed(square)(i) for i in range(1, 1000))

print(results)

Using this as a template it was fairly easy to re-work my finder script to call a compare_image function using joblib and aggregate the results in to one final list at the end. Playing around with the n_jobs variable I landed on 5 parallel image processing tasks before my CPU maxed out running them all. Below are the times on the same batch of images running different amounts of parallel processes. As you can see using 5 processes compared to 1 resulted in a 60% reduction in time. Not too bad for a minimal amount of changes.

| # of Images | # Parallel Processes | Time Taken |

| 122 | 1 | 16.7 minutes |

| 122 | 3 | 8.5 minutes |

| 122 | 5 | 6.7 minutes |

Making It Portable

I now had a pretty decent facial detection tool that could process images in parallel in a reasonable amount of time. The final hurdle was to make it portable so I could bring it places where I wanted to scan for pictures. This was the real end goal since I wanted to bring it to where the pictures were - relatives, friends, etc and be able to quickly find pictures of my own family we may be interested in saving.

My first pass at this was a project called Portable Python. The name alone sounded like it would hit the mark. Unfortunately this project hasn’t been updated since Python 3.2 in 2013 so I quickly threw out that idea. Instead I turned to the Embedded Python packages directly from Python.org. Extracting this gives you a full, standalone version of Python. The next problem was how to get dependencies up and running within this standalone environment. Generally for this you use a tool like the Python Package Installer. I needed to bootstrap this into my embedded environment. After some web searches, and a lot of trial and error, I hit upon a series of steps that successfully got the required libraries in a place where the embedded Python interpreter could find them. These are detailed in the README document for this project.

Once this was figured out I could move the entire project directory wherever I wanted and still run the image detection tool. For my use case I just carry it around on a USB Drive.

Final Thoughts

Once I figured out the portable piece of this project it was actually pretty fun to carry around and try it out. While it is a simple few steps it did take several hours of web searching to figure that part out so I’m impressed I even got it to work in the end. The detector itself does take some time and isn’t 100% accurate. Especially for photos where the target person is not the focus of the frame, or has their face turned to the side it does especially poor. In testing it found more than 90% of images for a target out of about 1000 test images. I thought this was pretty decent.

As an added bonus I added one last option --copy. This copies all the found images to a directory at the end of the program run. Using this I’ve been able to quickly plug in a USB, launch the script, and come back later to a folder full of images. Especially for family photos this has been fun to hunt down pictures saved all over a relative’s computer. I never did get around to trying it at work where I came up with the idea, maybe some day.